It’s a pleasure for the Burton at Bideford to be working with Professor Simon Olding again, the following article has been written by Professor Simon Olding in reference to our current exhibition ‘G-coding the collection’ by artist Michelle Shields.

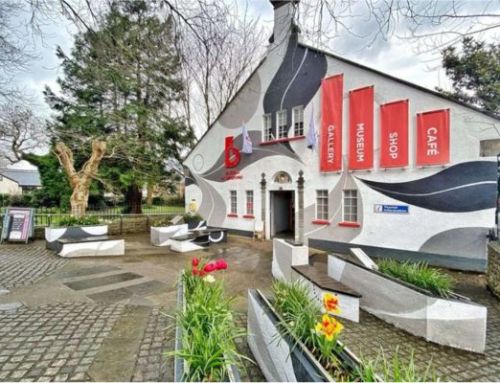

In 2009 I joined a team charged with two interlocking projects. The first was to help the Burton Museum & Art Gallery in Bideford (now the Burton at Bideford) to raise funds principally from the public purse to enable them to acquire the remarkable R. J. Lloyd ceramics collection. The second was to establish the case for lottery funds to create a purpose-built gallery to display the collection. Happily, both projects were successful and major grants were raised from the Heritage Lottery Fund, Art Fund, and the Victoria & Albert Museum Purchase Fund. Additional support came from the Bideford Bridge Trust and the exemplary Friends of the Burton Art Gallery & Museum, demonstrating local support and enthusiasm for this pioneering project.

The project was an articulate demonstration of the foresight of the enterprising museum staff, the underpinning axis of the local authority, and the engagement of the local community. There were additional activities, including the publication of a small book, Th R J Lloyd ceramics collection: artist as collector. I had the agreeable job of editing and writing for the book: bringing together texts from Alison Britton (her essay was memorably called ‘Laying the table: synthesis, continuity and the everyday’) as well as a fascinating conversation between exhibition curator Warren Collum and Reg Lloyd himself.

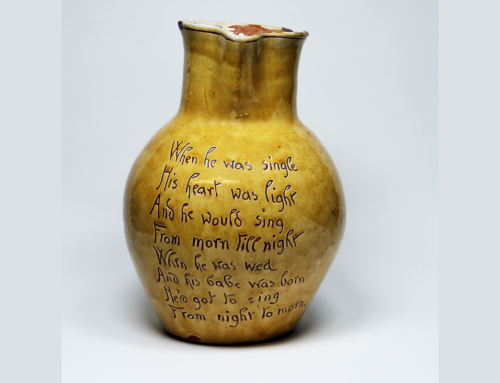

Michelle Shields came across this publication by chance in the library of the University for the Creative Arts in Farnham where she works as Technical Tutor in the ceramics department. It sparked an itching interest in the collection: in Lloyd’s intertwining work as an artist, and his life long collecting. It encouraged in her a deeper reflection and research enquiry based on the narrative of North Devon slipware, a ceramic story which runs deep in Bideford’s history as it does throughout North Devon. Lloyd’s collection was rooted in the local place (though it also included examples of slipware drawn from across the UK). It was also agreeably idiosyncratic: running from the rare to the pot of daily use; from the celebrated studios of Bernard Leach and Michael Cardew to the anonymous vessel; from the plain to the pictorial.

Wonderful Harvest jugs stand in the centre of this clay accumulation: marked for the season, ship or centenary to accompany, we may suppose the joy of carousing, as they are full bellied to hold ale or cider. This is domesticity, so the speak, smiling at the party.

2.

Michelle Shield’s work, made in compelling response to the collection, is both ceramic and ceramic-like, within and without the genre, and is interspersed among Lloyd’s collection in the gallery. Her pots and ‘pots’ are situated on the shelves and in the cabinets, not as interlopers but as communicants. They speak for themselves and this present time; and they have employed present available tools, whether analogue or digital, as needs be. They offer a refrain back to the past when ceramic work was fundamentally hand-made, or as Lloyd would have said ‘in the old manner’ (and the essential tools aided hand work). But the use of technology, fundamental to her project, is not done to point out the shortcomings of these past methods; it is used to celebrate them through re-imagining and reconfiguration. She has written an elegy for the old ways; and as a counterpoint to her digital pots, she has thrown, slipped and glazed her own ‘conventional’ vessels. She suggests in this dual approach of the analogue and the digital, that any or all ceramic methods are appropriate and fit for purpose, and that they can be a just starting point for contemporary research, analysis and makings. The scanned works made not of clay but corn starch derived bioplastic are there to hold a conversation with the original, to abstract out of it a new contrapuntal artefact.

What she has found, I think, precisely because her work is located in the analysis and deep seeking of Lloyd’s bravura, canny collection, is digital nuance and spectral surprise. All is not as it may first seem. There are replicated whole pots, scanned and printed; there are ‘half-pots’, true to form but made without clay. The blasting white of these digital examples sets out a complete contrast to the honey-glaze and harvest yellow of Lloyd’s originals. They are its ghosts of time present.

3.

Michelle Shields use of 3D scanning and printing techniques has been introduced as a companion technique to the time-honoured methods of throwing, glazing and hand marking. Each approach is seen as legitimate in the context of her roles as maker and as curator of this exhibition. She has, as it were, also re-curated the display of Lloyd’s pots, in order to re-see them. This reflects well on her creative vision, and it reflects well on the Burton at Bideford for trusting her to ask questions of the display and the collection that they may not have imagined were needed. It is a process that allows both for creative and curatorial change; and a sort of ceramic archaeology, because by digitally recording the collection, she has created a new artefact record, offering a new way of understanding these precious historic pots into the future. Furthermore, a dynamic education project was where Shields ran public workshops to create over 50 Harvest Jugs (also displayed in the gallery) enabling personal reflections on this ceramic heritage.

This is an exhibition that celebrates the past and present; geometry and calculation; tradition and the contemporary. It proposes that R J Lloyd’s collection is not a fixed point of collecting and historical record. It is a beginning for new creativity. Reg himself talked about finding a pot made by Edwin Beer Fishley in the markets at Bath. He remarked that ‘I could not believe this pot was so advanced. It’s ahead of its time’. Michelle Shields has paid the collector her own tribute and respect, by looking at his collection of slipwares of ‘the old manner’ and making work also ahead of its time.

Simon joined the University for the Creative Arts in the year 2002 as Director of the Crafts Study Centre, the university museum of modern craft. He joined the professoriate in 2004 as Professor of Modern Crafts. He is a supervisor for PhD students in the craft field and its related aspects.

His previous career includes working as a specialist ceramics curator, as a museum director (Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum, Bournemouth) as well as periods in agency and advisory work (London Museums Officer and Assistant Director, Area Museums Service for South Eastern England) and as Director of Policy and Research for the Heritage Lottery Fund. After graduating from Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, he received his PhD from the University of Edinburgh in 1980 for a study on ‘The English short story in the 1890s’.