Bideford Witch Trial: Prejudice and scapegoating in 17th century Devon

Individuals or groups can often be singled out by their communities and labelled because they don’t fit in. Known as “othering”, this often influences how people look at or treat, those who are seen as different or not behaving as expected. Negative characteristics, perhaps identified by name-calling, are often to these people or groups to single them out.

During periods of community conflict, scarcity or political and social change – “othering” can become a way for communities to define who does or does not qualify as a community member. If they are outside the community, do they deserve access to resources, or are they a potential threat to them?

Temperance Lloyd, Suzanna Edwards and Mary Tremble were accused of being witches before and during their trial in 1682. Temperance Lloyd had previously been tried and acquitted of causing death by witchcraft, but not Mary Tremble or Suzanna Edwards. Prior to their trial, the citizens of Bideford had faced great hardship. They had lived through, the English Civil War, outbreaks of the plague, 1682 was still a time of religious and social imbalance.

The three women were poor, abandoned, unmarried, or widowed and each lived off community funds. Thought of as outcasts, they were treated as ‘others’ by Bideford citizens. At the time two other women, of good means and family were also arrested for witchcraft but never went to trial.

All three women were, in quick succession, jailed in Bideford. They were searched for marks on their bodies and interrogated by their accusers – even before they arrived in Exeter for the trial. They were found guilty and executed in public on August 25th 1682.

Magpie

An unexpected visitation by a magpie, a creature associated in British Folklore with the Devon, was a crucial event in the story of the witches. The bird flew into the home of a woman suffering from an illness that local doctors suspected were caused by witchcraft. The appearance of Temperance Lloyd at the house, at the same time, was taken to mean that it was her familiar spirit, a creature that Lloyd used to deliver her harmful magic.

Apple

Temperance Lloyd had neem selling apples in Bideford when one was taken from her by a little girl. The child’s mother laughed the incident away and refused to pay Lloyd who expressed anger at the time. Lloyd was later accused of having cursed the child when some weeks later she fell ill. Oliver Ball, a local apothecary called in to help was unable to cure the girl and agreed that witchcraft was the likely cause of her illness.

Adolf Hitler Pin Cushion

Pushing pins into images, or in the case of the Bideford witch trial strips of leather, is often imagined as a way to magically injure others. As a modern example of this practice, this novelty pin cushion was manufactured during World War II in the United States. This practice of symbolically injuring others also appears in the burning of effigies or the toppling of public statues.

Bellarmine Jar

In the 17th century, Bartmann or Bellarmine jugs were used as ‘witch bottles’. These bottles, filled with various materials such as human urine, hair and pins were believed to be an effective countermagic to ward off witches.

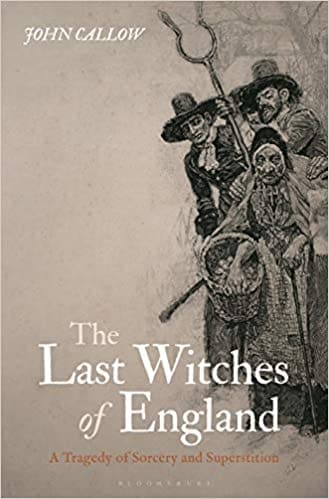

Quote from John Callow

“You wouldn’t have wanted to have known them.

You may well have come to avoid their stare, side-stepping them in the street, and fearing their presence, hovering, at your door.

Yet, the memories of the witches remained in Bideford. They were never quite ‘worn away’.

The recovery of that memory is, for me, very much part of a People’s History: of the world seen from below. Strip away the vitriol, the lies, and the twisted webs of superstition: and what remains are the life stories of three poor women who were marginal in every way that mattered in Seventeenth Century Europe. They were marginal in terms of their gender; in terms of their advanced age; in terms of their abject poverty; and in terms of their friendlessness and abandonment by their families.

In writing The Last Witches, it was important to give the three women – Temperance Lloyd, Susanna Edwards, and Mary Trembles – their voice and a measure of dignity, and of understanding, that they had been repeatedly denied during their lifetimes.

This act of recovery was made possible, in large measure, by the survival of the remarkable records of the John Andrew Dole, where the stories of Bideford’s poor come alive, unvarnished and largely unmediated. As a result, it is possible to reconstruct the outlines of the lives of the Bideford Witches that lay outside the conjecture, capricious malice and murderous hatred of others. What emerges is a world away from the tales of dark and maleficent magic: the raising of storms and the slaughter of innocents. It is an altogether more human account of lost hopes and opportunities, broken promises and tragic misunderstandings. Most of all, it is a tale of sheer bad luck.

And, it is all the more potent for that. If The Last Witches captures something of the pathos of the women’s fate, the sharpness of the prejudice they suffered, and the enormity of the divide that separated them from the comfort and plenty that characterised mainstream, mercantile Bideford – then it will have fulfilled its purpose.“

John Callow, author of The Last Witches of England: a tragedy of sorcery and superstition (2022) and Honorary Research Fellow at Suffolk University.

An Interview with John Callow:

Buy the book The Last Witches of England by John Callow

This display is also available to view in the Burton at Bideford Museum.